| contents

| introduction

| what

is river basin management? | water

21rbm research | results:

rbm in five countries | conclusions

| the

framework directive in the light of water 21 |

summary

This

paper presents the research from the Water 21 project on river

basin management (rbm) and analyses the proposal for a framework

directive on water in the light of the conclusions of this

research. Water 21 is a collaborative research project involving

teams from five European countries (France, Germany, The Netherlands,

Portugal and the United Kingdom), seeking a comprehensive

appraisal of water policies in Europe in terms of sustainability.

As part of the project, research as conducted on the different

instruments and approaches used in rbm in these five countries

and in six transboundary river basins. Support was found for

the initial theory that co-operation between the different

managers, user involvement and the use of expertise promote

effective, sustainable rbm. Another conclusion is that rbm

should always combine generic and river basin specific instruments

and approaches. The proposal for a Framework Directive Water

reflects these conclusions only partially.

introduction

River

basins are important management units. River basins are the

natural context in which freshwater occurs. They are the ultimate

source of all water used in households, agriculture and industry

and the receptor of most wastewater. Moreover, the waters

in river basins have important non-consumptive uses, such

as recreation, nature, fishing and hydropower production.

Consequently, effective river basin management (rbm) is imperative.

Rbm

is not a new topic, but recently attention has been increasing.

In Europe the most notable facts are the signing in 1992 of

the UN-ECE Convention on the Protection and Use of Transboundary

Watercourses and International Lakes (UNECE 1992); and the

proposal of the European Commission for a Council Directive

establishing a Framework for Community Action in the field

of water policy (Commission 1997). The Helsinki Convention

and the Framework Directive raise important implementation

questions, which have to be solved in the very near future.

Against

this background rbm was chosen as an important topic in the

Water 21 project. Water 21 is a collaborative research project

seeking a comprehensive appraisal of water policies in Europe

in terms of sustainability. Five universities and research

institutes from five European countries are involved in this

project: France (LATTS), Germany (Ecologic), the Netherlands

(RBA Centre, TU Delft), Portugal (IST, co-ordinator) and the

United Kingdom (WRc). The project is funded by the Environment

Research Programme managed by DG XII of the Commission of

the European Union, with additional funds provided to some

teams by national organisations.

This

paper presents the research within Water 21 project on rbm

and analyses the proposal for a Framework Directive in the

light of the conclusions reached. It will pay attention to

the following topics:

What

is river basin management?

- Water

21 research on rbm

- The

results: rbm in five countries and six international basins

- Conclusions

of the project

- The

Framework Directive in the light of the Water 21 conclusions

This

paper is based on the Water 21 report "River Basin Management

and Planning; Institutional structures, approaches and results

in five European countries and six international basins" (Mostert

ed. 1999), which contains much more details and references.

what is river basin management?

Central

in the notion rbm is of course the term river basin. A river

basin is the geographical area determined by the watershed

limits of the system of waters, including surface and underground

waters, flowing into a common terminus (cf. art. II of the

Helsinki rules). However, river basins are not just geographical

areas. What turns the area into a unit are the strong relations

between the different constituent parts and elements: land

and water, groundwater and surface water, quantity and quality,

upstream and downstream. For instance, an increase in agriculture

and use of pesticides upstream can decrease the quantity and

quality of the water available downstream. Through mechanisms

such as these "water and soils" in the river basin "come i nto

some sort of integration" (Lundqvist et al. 1985: 14). nto

some sort of integration" (Lundqvist et al. 1985: 14).

It

has to be noted that river basin boundaries are sometimes

ambiguous and always permeable. Some rivers traditionally

seen as separate have a common estuary (e.g. the Rhine and

the Meuse) and could be seen as belonging to one river system.

Moreover, in "natural" flatland areas water flows are rather

erratic, and in engineered flatlands determined (and alterable)

by means of canals, sluices and pumps. Finally, aquifer boundaries

and the watershed for surface waters never coincide exactly

and sometimes are completely different. Finally, river basins

are not closed systems. They interact continuously with the

atmosphere (precipitation and evaporation, airborne pollution

etc.) and the receiving waters (seas and sometimes lakes).

In addition, the uses made of river basins often transcend

river basin boundaries. For example, hydropower produced in

one basin may benefit areas in other basins, and water for

irrigation and drinking water supply may be transferred from

one basin to another.

Whether

clearly demarcated or not, river basins have to be managed

carefully. This is quite difficult, given the very diverse

characteristics of rbm. (Box 1, next page) The Water 21 project

studied how the challenge could be met best.

- multifunctionality

River

basins perform numerous functions, such as fishing, water

supply, hydropower generation, recreation and nature.

Often these conflict. River basins may be developed to

perform the different functions better, but this is often

costly. Consequently, the different functions have to

be balanced against each other and against the costs they

entail.

- users

River

basins with many functions automatically have many types

of users with different interests. This implies that balancing

functions is not a neutral activity.

-

managers

Most

basins have many managers. Even if all water management

is in one hand, relevant aspects of other policy sectors

(land-use, agriculture etc.) are not. As each managerís

competencies and capacity are limited, they are dependent

on each other for achieving their goals and should therefore

co-operate. At the same time, there are ample possibilities

for conflict as the different managers usually represent

different (mixes of) interests. Especially in international

basins conflicts may occur, due to cultural and language

differences, the additional (international) government

level involved, differences in national goals, and the

absence of an effective international judiciary and executive

able to decide in controversial issues.

- Asymmetric

power relations

A

special characteristic of rbm, complicating it even further,

are the asymmetric power-relations caused by hydrological

factors. To overstate the issue: the downstream users

and managers are at the mercy of the upstream users and

managers. Power asymmetry is, however, never total. On

other issues the "upstreamers" may depend on the "downstreamers"

(e.g. maritime access), and the former may appeal to the

goodwill of the latter. 5. Technically complex A last

characteristic of rbm is its technically complex character.

As there are so many different interrelations in river

basins, it is difficult to foresee the effect of specific

measures. Therefore, extensive research may be necessary.

- Technically

complex

A

last characteristic of rbm is its technically complex

character. As there are so many different interrela-tions

in river basins, it is difficult to foresee the effect

of specific measures. Therefore, extensive research may

be necessary.

water

21 rbm research

eurowater,

the predecessor of Water 21 eurowater,

the predecessor of Water 21

The

Water 21 research on rbm built on the research on rbm in the

Eurowater project, which was like the Water 21 project a European

research project, sponsored by the Euro-pean Commission, DG

XII, and with the same partners. The Eurowater project studied

and compared the different institutions for national rbm in

the five Eurowater/ Water 21 countries (Betlem 1998) and identified

three different institutional models:

The hydrological model (management by river basin authorities)

The administrative model (management not based on river

basins at all)

The co-ordinated model (co-ordination at the river basin

level)

As

argued elsewhere (Mostert 1998), each model has advantages

and disadvantages - the administrative model primarily disadvantages.

Moreover, the hydrological model may not be feasible in countries

with a high degree of decentralisation and in international

basins. Furthermore, it was concluded that the specific instruments

and approaches used in rbm are at least as important as the

institutional model - and easier to change.

scope

and research question

In

the Water 21 project, river basin management was selected

as one of three dimensions of water management deserving special

attention, the other two being water services pro-vision (water

supply and wastewater treatment), and subsidiarity. River

basin manage-ment was taken in a broader sense than in Eurowater.

It includes all activities, whether from the public or the

private sector, that aim at a better functioning of the water

system in river basins and the land in as far as relevant

for or depending on the water system. Thus, it includes not

only water management in a strict sense, but also large parts

of land-use planning and agricultural and industrial policy.

Moreover, the Water 21 project did not only consider national

basins, but also international basins. The main focus was

not on institutional models, but on the specific instruments

and approaches that can be used in rbm.

The

basic theory used was very simple. We assumed that rbm systems

should be judged by the results that they yield and not by

their institutional form or "theoretical beauty." We define

effective rbm as rbm that ensures that river basins fulfil

their different functions in a satisfactory way, and will

continue to do so into the foreseeable future. We furthermore

hypothesise that three factors promote such results: co-operation

between the different managers, user involvement, and the

use of expertise. Consequently, the instru-ments and approaches

used in rbm should stimulate co-operation, user involvement

and expertise.

Based

on this theory, we addressed three questions:

Which instruments and approaches for rbm are used in the

Eurowater countries and the selected international basins?

Do these instruments and approaches, promote co-operation,

user involvement and the use of expertise, given the specific

hydrological, socio-economic and institutional con-text?

Do co-operation, user involvement and the use of expertise

promote effective rbm?

The

ultimate aim was twofold: to increase insight in rbm; and

to support the choice of instruments and approaches at the

national and the EU level and in international basins.

research

methodology

The

research used the case-study approach (Yin 1986). First a

theoretical framework was developed (basically a specification

of the basic theory). Following case descriptions were prepared

in order to test and illustrate the theoretical framework.

Finally, the cases were compared carefully, conclusions were

drawn concerning the instruments to be used in rbm, and the

theoretical framework was adapted and enriched.

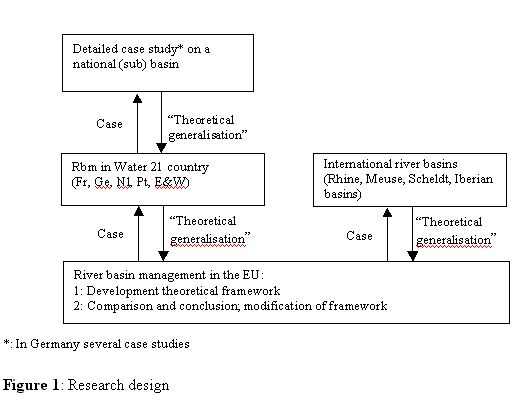

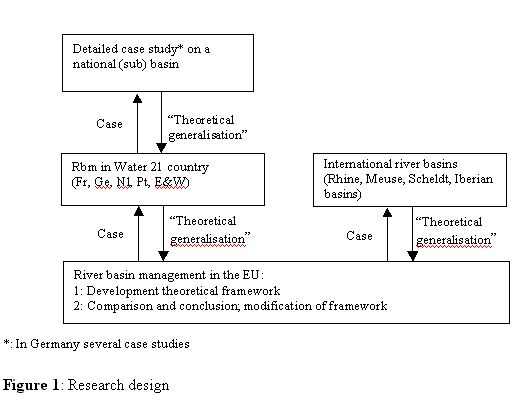

Cases

were conducted at two levels. The "first order" case studies

are the descriptions of rbm in the five Water 21 countries

and descriptions of the management of six selected international

river basins. The second-order case studies were individual

basins within the five countries. (Figure 1,below)

Research

teams from all countries studies were involved, co-ordinated

by the co-ordinator for the Water 21 topic rbm, the Dutch

team. The co-ordinator drafted the theo-retical framework

and terms of reference for the case studies in co-operation

with the other team. Following, each team conducted its national

case study, and some teams also an international case study.

These case studies were reviewed by the co-ordinator to safe-guard

consistency.  Finally,

the co-ordinator drafted the conclusions, which were dis-cussed

with all other teams. Finally,

the co-ordinator drafted the conclusions, which were dis-cussed

with all other teams.

results:

rbm in five countries and six international basins

instruments

and approaches

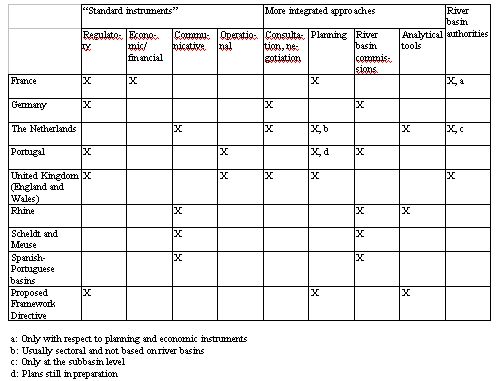

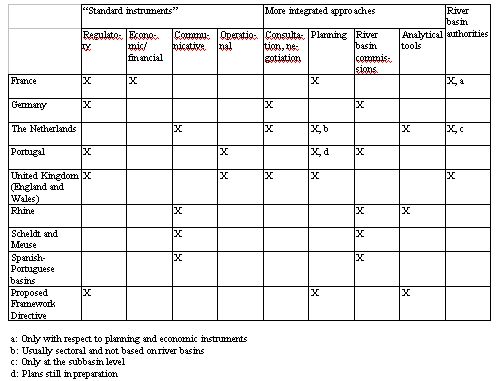

The research has resulted in the first place in an overview

of rbm systems in the different countries and international

basins studied. In most countries and international basins

all instruments and approaches can be found, but their popularity

differs quite a lot (Table 1, next page). Moreover, even if

in two countries the same instrument or approach is popu-lar,

these may still be implemented quite differently. For instance,

in the Netherlands the function of planning ranges form policy

preparation, to strategy formulation and to co-ordinating

and prioritising individual activities and projects. In England

and Wales, on the other hand, emphasis is very much on the

last function of planning.

table

1: most popular instruments and approaches in river basin

management

co-operation,

user involvement and use of expertise

The

degree of co-operation, user involvement and use of expertise

too differs between the different countries and basins. In

France, the new (1992) river basin planning system has improved

the co-operation between the managers and the involvement

of the users. The bodies that exist at the basin (Agences

de l'Eau) and the subbasin level (Local Water Commissions)

include representatives from different government bodies and

user groups, albeit the latter as a minority. Moreover, the

Local Water Commissions improved the use of expertise significantly.

They produce a lot of information and their board composition

adds legitimacy to the information.

In Germany co-operation between managers is extensive,

especially in river basin commissions with a co-ordinating

task and in professional organisations. Some problems,

however, persist (e.g. the in the relation between waterway

management and water man-agement). Different user groups

can participate in the many water users associations,

which execute parts of German rbm, such as river maintenance

or sewage treatment. Ex-pertise too plays a big role.

Technical guidelines produced by technical-scientific

associa-tions and their working groups are often generally

accepted and function as technical standards.

In The Netherlands, co-operation between the managers

is usually satisfactory. The planning system, the several

steering groups and commissions, and the Dutch consensus

culture imply that there are many contacts between the

managers. Still, co-ordination problems do occur, for

instance within the provinces and between the waterboards

and municipalities. The users can participate in the waterboards

and in planning, but still some many managers like to

keep control over management and limit the role of the

us-ers. The use of expertise in Dutch rbm is extensive,

especially at the national level. The expertise available

at the smaller municipalities is often limited.

In

Portugal, in the absence of integrated planning, co-operation

between the different managers is on an ad-hoc basis.

Still, co-operation between the central and local powers

is generally effective. Conflicts that do arise derive

often from disagreements over the financing of certain

planned works. User involvement takes several forms. They

can par-ticipate in users associations, in river basin

councils for the big basins, and in the prepara-tion of

the municipal master plans. The use of expertise is still

limited, and most informa-tion available to managers is

sectoral in nature.

In

the England and Wales co-operation between water managers

is high, with many water management functions integrated

in one organisation, the Environment Agency. Co-operation

with land-use planners has traditionally been limited,

but several efforts are being made to improve co-operation.

The Environment Agency actively consults the lo-cal authorities,

NGOs and segments of the public in the so-called LEAP-process.

The use of expertise in rbm is extensive.

In

the international basin the major issue is international

co-operation.In this respect the Rhine clearly takes the

lead of all international basins studied. Countries co-operate

in the framework of the International Rhine Commission

since 1950, and since a few years also international NGOs

can participate directly in the Commission's work. Expertise

has always played a central role in the International

Rhine Commission. There is joint moni-toring, the main

emission sources have been inventoried, etc. As in the

case of the Local Water Commission, the presence of a

legitimate institution has given the reports and in-formation

produced the force of greater integrity.

In

the Meuse and Scheldt basins international co-operation

is of a more recent date and has not yet developed in

the same degree. Moreover, user involvement seems to be

more limited. Expertise again plays an important role.

In

the Iberian basins one should distinguish between two

periods with quite different issues. Until 1993, co-operation

on boundary issues and hydropower issues was effective.

Gradually, however, possible future water shortages and

water pollution became impor-tant, and in November 1998

Portugal and Spain agreed on a new convention with a broader

scope. The role of expertise in the management of the

Iberian basins is not as ex-plicit as in the case of the

other basins studied.

results

in the basin results

in the basin

As

stated before, rbm systems should be judged by the results

that they yield and not by their institutional form or "theoretical

beauty." Looking at the results, we can see that in each country

and international basin studied a number of problems have

been solved or are being solved and a number of problems still

await solution.

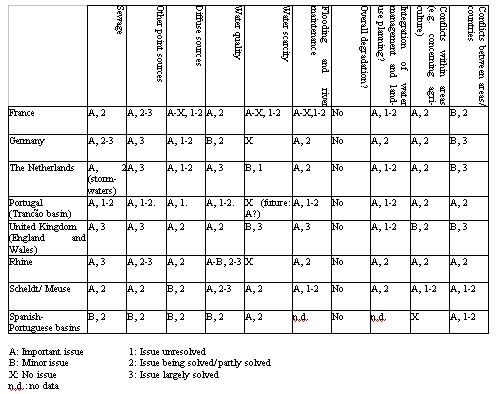

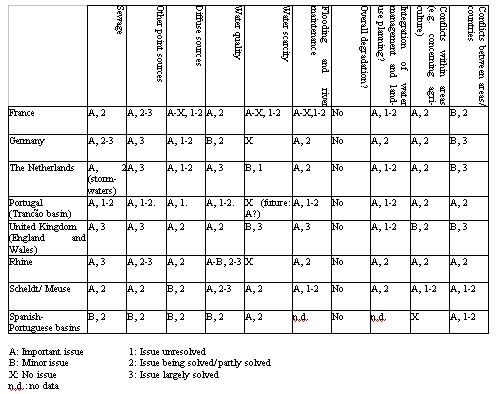

table

2: results of river basin management: reflecting as much as

possible regional differences within countries and basins

(indication only!)

The

unsolved and solved problems differ, but flooding is a problem

in all cases. Usually, there is no overall degradation of

the basins, but significant degradation does occur in the

form of overexploitation of water resources (e.g. some parts

of France), erosion (e.g. the Tranc„o basin in Portugal),

groundwater pollution (e.g. the Netherlands), illegal construction

of levies along the river (e.g. the Arc river in France) and

eutrophication (e.g. the Netherlands). The integration of

water management and land-use planning is usually limited.

Conflicts

between upstream and downstream parts of a basin and upstream

and down-stream countries occur, but they usually do not lead

to bad relations; "water wars" be-tween the Water 21 countries

are presently unthinkable. More important are conflicts within

areas. In all countries studied there are major unresolved

conflicts between urban development and flood protection (e.g.

developments in flood-prone areas) and between agriculture

and environmental protection (diffuse pollution, water use).

Moreover, sew-age is a problem (stormwaters everywhere, treatment

in some countries). Industrial pollu-tion has been tackled

effectively in most countries.

Ultimately,

the major conflict in all countries and international basins

studied is a so-cial and economic one. Although in the long

term sustainable rbm is cheaper than unsus-tainable rbm, in

the short term it is more expensive. In the short term priorities

have to be set between economic development now or better

circumstances - also economically - in the (far) future. The

result can only be sustainable if environmental consciousness

is high, if a long-term perspective is used, and if effects

in the whole basin are taken into account, including transboundary

effects.

Table

2 summarises the results of rbm in the different countries

and international ba-sins. For several reasons it has proven

difficult to assess the results. The amount of in-formation

on the status of the river basins differs substantially and

the information is not totally comparable. Moreover, improvements

or lack of improvement cannot automati-cally be attributed

to the management of the basin: external factors such as socio-economic

and technological developments are important too. Still, Table

gives an im-pression.

conclusions

co-operation,

user involvement and use of expertise

After

studying rbm in five countries and six international basins,

the basic theory that co-operation, user involvement and use

of expertise promotes effective (=sustainable) rbm still stands.

Some parts of the basic theory have been confirmed by one

or more of the cases studied, some parts could be developed

further, inspired by the information gath-ered form the cases,

and no part was falsified.

The

need for co-operation is recognised in most countries and

basins studied. The subbasin studied in Portugal, the Tranc„o

basin, offers a clear example of this need. In this basin,

effective co-operation between the agencies responsible for

land-use planning and those responsible for flood protection

has been largely lacking. This has lead to the adoption of

expensive infrastructural measures for reducing flood risks,

such as dykes, instead of non-structural measures, such as

reforestation upstream, that could also en-hance the nature

and recreation value of the basin. In the Netherlands the

need to co-operate has even resulted in the famous "consensus

culture," which tries to avoid con-flicts in order to keep

good relations (also as a means of "self-defence", to prevent

that others infringe upon your position).

The

importance of user involvement too is widely recognised. Yet,

two different forms should be distinguished: management by

the users, and involvement of users in manage-ment activities

by governmental bodies or the water industry. Examples of

the former can be found in for instance Portugal (users' associations

in agriculture), Germany (water us-ers associations), and

the Netherlands (the waterboards). Management by users makes

management, which usually also implies financing by the users,

makes management in-dependent from government and its political

allocation of funds. It provides optimal con-ditions for balancing

costs and benefits of water management activities, but since

the wa-ter users' associations usually deal with only some

aspects of rbm, co-ordination with other the other aspects

is a very important issue. The

importance of user involvement too is widely recognised. Yet,

two different forms should be distinguished: management by

the users, and involvement of users in manage-ment activities

by governmental bodies or the water industry. Examples of

the former can be found in for instance Portugal (users' associations

in agriculture), Germany (water us-ers associations), and

the Netherlands (the waterboards). Management by users makes

management, which usually also implies financing by the users,

makes management in-dependent from government and its political

allocation of funds. It provides optimal con-ditions for balancing

costs and benefits of water management activities, but since

the wa-ter users' associations usually deal with only some

aspects of rbm, co-ordination with other the other aspects

is a very important issue.

Involvement

of users in management activities by governmental bodies is

very com-mon, and in water industry very rare and limited.

Benefits are (1) all legitimate interests may be heard; (2)

more information and creative ideas become available for manage-ment;

and (3) management may become more legitimate and accepted.

Yet, to realise these benefits a number of criteria have to

be met. First, all different user groups should be represented.

From the point of view of sustainability, it is especially

important that environmental NGOs are represented. Secondly,

the different managers should take user involvement serious,

but at the same time take their own responsibility. If user

involve-ment is not taken seriously, useful information is

not used, specific interests may still be overlooked, and

legitimacy and acceptance may actually deteriorate. Yet, however

seri-ous managers take user involvement, they cannot "hide"

behind user involvement and say they just do what the public

wants. They should take their responsibility for their actions

and have to be hold accountable for their actions. To prevent

disillusion on the part of the users, the role of user involvement

and the responsibility of the managers should be made clear

at the beginning. Thirdly, environmental awareness of the

public should be at least as high as among the managers, and

public information on the issues at stake and on en-vironmental

issues generally should be good.

It is unclear what the role of user involvement should be

in international basins. One could argue that responsibilities

in international rbm could become too diffuse and rbm itself

too complex if user groups are involved directly in the work

of river basin commis-sions, which are basically just platforms

for co-operation between the basin states. An alternative

form of user involvement would be involvement through the

different basin states, at the national level. However, river

basin commissions, and particularly the secre-tariat of these

commissions, play to some extent an independent role, and

this would point to user involvement at the basin level. Moreover,

since a few years, the Interna-tional Rhine Commission actively

involves international NGOs in its work, to the satis-faction

of both the Commission and the NGOs.

The

use of expertise is beyond doubt essential for rbm. Rbm implies

balancing con-flicting functions and is therefore highly political,

but if this balancing is not based on a sound understanding

of the issues at stake, the result is unlikely to be satisfactory.

Exper-tise is used extensively in most countries and basins

studied. An important issue turns out to be the acceptability

of research for the parties concerned. The Local Water Commis-sion

on the Arc and the International Rhine Commission show that

the involvement of a legitimate, joint institution can significantly

enhance acceptability.

instruments

and approaches

Having

made plausible that co-operation, user involvement and the

use of expertise in-deed promote effective, sustainable rbm,

the question is now what instruments and ap-proaches can be

used for this purpose. Moreover, we will present additional

insights on the use of instruments and approaches that have

emerged from the case studies.

Concerning

national rbm, the first conclusion is that river basin specific

and generic instruments and approaches should be combined

- as indeed they are in the cases studied. The limitation

of most generic instruments (e.g. EU-wide emission or water

quality stan-dards) is simply that they cannot take local

circumstances into account. Consequently, if all rbm were

generic, rbm would be much too strict in many basins, or much

too lenient in other basins, or a combination of both. The

limitations of river basin specific instru-ments and approaches

are, first, that many factors impacting on river basins are

not lo-cated in the basin (cf. atmospheric pollution and EU

agricultural policy). Secondly, it is more difficult to ensure

a minimum level of environmental protection if everything

is de-cided upon with the different river basins. Thirdly,

too big differences between basins or subbasins may affect

the competitiveness of the local industry, and this may form

a drive towards lower levels of environmental protection.

And fourthly, information demands and required expertise are

usually much higher.

Secondly,

many of the cases studied (e.g. France, The Netherlands and

Portugal) show the shortcomings of regulatory instruments.

Regulatory instruments are difficult to en-force, especially

when regulating many small activities, and strict regulation

is often not politically feasible. To overcome these shortcomings,

instruments based on communica-tion and persuasion are increasingly

used, but these instruments have their limitations too. Users

will not agree voluntarily with anything that goes against

their interest, unless there are some specific positive or

negative incentives - such as the possible future regulation.

Consequently, one cannot abandon regulatory instruments totally,

and work needs to be done on improving enforcement and increasing

the necessary social and political support for this.

Thirdly,

systems of planning and river basin commissions offer good

possibilities for improving co-operation between managers

and organising public participation and exper-tise. They bring

managers together, may offer a framework for public participation,

and constitute an obvious focus for organising policy-relevant

research. What is not possible for the, many, individual operational

decisions (e.g. granting of permits) may be possible for one

or two planning processes or for one or two commissions. Apart

from this, as al-ready discussed, commissions may give legitimacy

to research results. Thirdly,

systems of planning and river basin commissions offer good

possibilities for improving co-operation between managers

and organising public participation and exper-tise. They bring

managers together, may offer a framework for public participation,

and constitute an obvious focus for organising policy-relevant

research. What is not possible for the, many, individual operational

decisions (e.g. granting of permits) may be possible for one

or two planning processes or for one or two commissions. Apart

from this, as al-ready discussed, commissions may give legitimacy

to research results.

The

need for a commission was felt especially in the Portugal

at the subbasin level. In the Netherlands, on the other hand,

there is a profusion of commissions and planning, which sometimes

decreases transparency and consistency. In other words, there

can be too much of a good thing. Apart from that, planning

and commissions should be directed towards operational decisions

if they are to improve rbm, but these decisions should be

set within a long-term vision on the pertinent basins. Moreover,

if the plans are to be im-plemented, there should be a clear

link between the different operational plans and budg-eting

procedures.

Fourthly,

river basin authorities exist only to a very limited extent

in the countries studied. River basin authorities can potentially

deal effectively with upstream-downstream problems: by definition,

they cover the whole basin and can take binding decisions.

A weak point is that most are not competent in land-use planning,

unlike for instance municipalities or provinces. This is presently

a very salient point, since many water management problems

are at the interface with land-use planning (flood protection,

diffuse pollution, erosion, desiccation).

Concerning

international basins, the major conclusions are first, that

international co-operation usually takes a long time to develop

and that trying to hurry the development may not be a good

thing. Secondly, disasters have proven to be a strong stimulus

to fur-ther international rbm (cf. the Sandoz disaster in

1986, which resulted in the Rhine Ac-tion Plan). Another means

to further international co-operation, and this is the third

con-clusion, is to link contentious issue with issues where

the distribution of costs and bene-fits is exactly the reverse

(cf. The Meuse and Scheldt negotiations). In this way conflict-ing

interests can be overcome. Fourthly, it may be advisable to

rely not only on interna-tionally binding agreements. As shown

by the Rhine Action Plan, non-binding agree-ments can be very

effective, and moreover they take less time to reach. Fifthly,

like in national rbm, river basin commissions with a co-ordinating

task have proven to be very useful.

Finally,

The EU provides a generic framework for water management,

which applies to all basin states of the international basins

studied (except Switzerland), but not specifi-cally to any

individual river basin. The previous discussion on generic

rbm versus river basin specific rbm applies here too, including

the solution proposed: combine the generic and the river basin

specific approach.

the

framework directive in the light of Water 21

A

very pertinent question at this moment is whether the proposed

EU Framework Direc-tive Water reflects the conclusions listed

above. Any discussion of this proposed Direc-tive should start

with the remark that its scope is limited. It deals with water

quality in an integrated way, but it covers only some aspects

of water quantity (overexploitation of groundwaters, effects

of droughts and floods). This is clearly a limitation.

Secondly,

the Directive combines generic rbm with river basin specific

rbm, but with the emphasis on the generic rbm. The Directive

is based on a river basin approach, but how these basins should

be managed is determined to a large extent in the Directive,

and not in the basins themselves. The Directive prescribes

what types of analyses should be performed, how often river

basin plans should be reviewed, what the environmental ob-jectives

for the river basins are, etc. Moreover, it pays very little

attention to subbasins.

The

Directive offers some flexibility, but within rather strict

limits. This limited flexibil-ity and emphasis on a generic

approach is to some extent understandable, since the level

of environmental consciousness differs quite considerably

between the different member states. Consequently, too much

flexibility could results in a totally different implementa-tion

of the Directive. On the other hand, the European Commission

will probably have very large difficulties in controlling

the implementation of the Directive in its present (June 1998),

complex form. The Directive's approach to pollution control

is a good example of the Directive's emphasis on a generic

approach. Pollution should be controlled primarily by means

of emission controls based on the Best Available Technique

or on the relevant emission standards. However, more stringent

emissions controls should be applied if this is neces-sary

to reach a relevant quality objective or standard. The Best

Available Technique, relevant emission controls, and the quality

objective and standards are largely generic. Yet, if applied

properly, the result of the combined approach will be river

basin specific pollution control that reflects the differences

in the different basins.

Thirdly,

the main policy instruments in the Framework Directive are

regulatory. Much emphasis is put on binding programmes of

measures, emission controls etc., and very lit-tle on instruments

such as voluntary agreement. This is rather problematic, given

the main shortcoming of regulatory instruments: limited compliance.

For the Directive to be effective, much attention should go

to enforcement, within the member states (compli-ance by water

users) and at the European level (enforcement policy of and

practice in the member states). Moreover, consideration could

be given to alternative policy instrument such as voluntary

agreements, without, however, forgetting their weak points. Thirdly,

the main policy instruments in the Framework Directive are

regulatory. Much emphasis is put on binding programmes of

measures, emission controls etc., and very lit-tle on instruments

such as voluntary agreement. This is rather problematic, given

the main shortcoming of regulatory instruments: limited compliance.

For the Directive to be effective, much attention should go

to enforcement, within the member states (compli-ance by water

users) and at the European level (enforcement policy of and

practice in the member states). Moreover, consideration could

be given to alternative policy instrument such as voluntary

agreements, without, however, forgetting their weak points.

Fourthly,

the system of river basin planning and the identification

of competent au-thorities offer good opportunities for improving

co-operation between managers and or-ganising public participation

- at least in purely national basins. Much, however, will

de-pend on the implementation of the Directive in the different

member states. The Directive does not say who should be involved

in planning and in what phase, other than that the draft rbm

plan should be put on public display and the public should

get the opportunity to comment in writing. The member states

have to ensure "the appropriate administrative arrangements,

including the identification of the appropriate competent

authority", but the Directive does not say what these arrangements

and what this competent authority should look like and how

they should function. Yet, issues such as these will determine

whether co-operation and user involvement will actually increase

or not. The Directive may promote co-operation between water

management and agriculture at the European level (DG XI and

DG VI of the Commission). According to art. 15, member states

may report important issues for rbm that lie outside their

competence, such as EU agricultural policy, to the Commission,

and the Commission then should respond within six months.

The

Framework Directive says relatively little about the management

of international river basins and is consequently unlikely

to improve international co-operation much. Ba-sically, each

member state should manage its part of international basins

and co-operate internationally where necessary. The Directive

says little about the form of co-operation or how it should

be developed. The pertinent member states should together

delineate their international river basins and assign them

to an international river basin district. Moreover, they should

try to develop an international rbm plan; their more operational

programmes of measures should only be co-ordinated. The Directive

does not require the establishment of international river

basin commissions. However, the establishment of river basin

commissions is required by the Helsinki convention, which

was also signed by the EU. (UNECE 1992)

REFERENCES

Betlem,

I. 1998: "River basin management and planning." in: F.N. Correia

(ed.): Water Resources Management in Europe. Volume 2: Selected

Issues in Water Resources Management in Europe. Balkema: Rotterdam.

Commission

of the European Communities 1997: Proposal for a Council Directive

es-tablishing a Framework for Community Action in the field

of water policy. COM(97) 49 def.

Lundqvist,

J.; U. Lohm; M. Falkenmark 1985: "Synthesis and conclusions."

in: idem (eds.): Strategies for River Basin Management; Environmental

Integration of Land and Water in a River Basin. D. Reidel

Publishing Company: Dordrecht/ Boston/ Lan-caster.

Mostert,

E. 1998: "River Basin Management in the European Union; How

it is done and how it should be done." European Water Management.

Vol. 1, No 3, 26-35.

Mostert,

E. (ed.) 1999: River Basin Management and Planning; Institutional

structures, approaches and results in five European countries

and six international basins. RBA Series on River Basin Administration,

Research Report nr 10. RBA Centre: Delft.

UNECE

(United Nations Economic Commission for Europe) 1992: Convention

on the Protection and Use of Transboundary Watercourses and

International Lakes. Pub-lished in (a.o.) Tractatenblad van

het Koninkrijk der Nederlanden, nr. 199.

Yin,

R.K. 1986: Case Study Research. Applied Social Research Method

Series, Volume 5. 4th Impression. Sage: Beverly Hills etc.

ADDED

REFERENCES

Outline

of river basin management: Outline

of river basin management:

Mostert,

E. et al. 2000: "River Basin Management and Planning", in:

E. Mostert (ed.): River Basin Management; Proceedings of the

International Workshop (The Hague, 27-29 October 1999). UNESCO,

IHP-V, Technical Documents in Hydrology, nr. 31, Paris, pp.

24-55.

The

Proceedings are available free of charge from the Distribution

Centre of the Ministry of Housing, Spatial Planning and the

Environment (order number 20066; address see above) and from

UNESCO (United Nations Bldg./ 2nd Floor, Jalam Thamrin 14,

1273/ JKT Tromolpos/ Jakarta 10012, Indonesia/ Fax : +62 21

315 0382/ E-mail : m.overmars@unesco.org). The paper is also

on the Internet http:/www.ct.tudelft.nl/rba/rba.htm.

Newer

version of the Framework Directive: Framework Directive Water

(1999) Common position (EC) No 41/1999 adopted by the Council

on 22 October 1999 with a view to the adoption of a directive

1999/Ö/EC of the European Parliament and Council Directive

establishing a framework for Community ac-tion in the field

of water policy. OJ C 343/01, 30.11.1999. http://europa.eu.int/eur-lex/en/oj/index.html

|